The Garden Within

“The successful gardener has always known you don’t need to master the science of soil in order to nourish it. You just need to know what it likes to eat- basically organic matter- and how, in general, to align your interests with the interests of the microbes and the plants. The gardener also discovers that, when pathogens or pests appear, chemical interventions “work”, that is, solve the immediate problem, but at a cost to the long-term health of the soil ad the whole garden.” -Michael Pollan The New York Times May 19th, 2013

While this quote may seem like it is from an article about organic gardening, it is from an article entitled “Some of My Best Friends are Bacteria” in which author Michae Pollan compares the microflora of our gastrointestinal tract with the soil microbes of a garden.

As an avid gardener and as a naturopathic doctor with a strong interest in gastrointestinal health, this comparison is one that I frequently think about while I have been tending my garden beds this summer.

In gardening we learn that if we nourish and build good soil the plants will grow well, and we will have a good harvest year after year. Plants tend to be resilient to diseases, and pests are often controlled by the beneficial insects that are attracted to a healthy diverse garden. In industrial agriculture (as well as in many backyard gardens), the focus is on getting the plants to grow as quickly, uniformly, and in as high of a volume as possible. The soil is depleted and does not contain the diversity of soil nutrients and microbes and so high levels of synthetic fertilizers must be given to the plants. The plants are susceptible to many diseases and pests and so they have to be treated (or genetically modified) in order to survive. This practice needs a high level of input, produces food deplete in nutrients and is not sustainable.

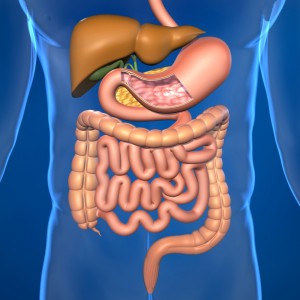

Our gastrointestinal tracts can be thought of in a similar way to the soil of the garden. The trillions of bacteria that inhabit our intestines play an integral role in promoting the health of their host (us). If we create an optimal environment for them to grown in, provide them with the nutrients that they need to survive, and ensure that we are growing a diverse population we will be rewarded with vitamins, decreased inflammation, optimal weight management, balanced immune function, and production of calming neurotransmitters to name but a few of the benefits.

If we create a less hospitable environment by starving them of the nutrients they need, killing them off with antibiotics from varied sources, and live our lives in such a sterile way that we don’t allow for diversity in our gut microflora, we may end up with many negative health consequences including increased inflammation, obesity, diabetes, allergies, gastrointestinal illnesses and autoimmune diseases to name but a few.

Our knowledge of the importance and influence of our gut microflora is in its relative infancy. While there is a great deal of research being done to learn more, we do not know enough to always have certainty as to what bacteria are “good”, what bacteria are “bad”, and what the effects of differences in the diversity of the bacteria may have on our health.

We do know enough to know that it is important to nurture and foster our garden within. While it can be changed by external influences, the microbial community is relatively stabilized by the time we are three years old. Exposure to bacteria through vaginal birth and breast feeding seems to have the major influence on how this community develops. While we can’t go back and change what occurred before we were three, there are steps that you can take to “help your garden grow.

- “Eat food, mostly plants, not too much”. While this quote is from an earlier Pollan work, In Defense of Food, its wisdom holds true for creating a healthy microflora population as well. The fibers and other polysaccharides in plant foods serve as the prime food supply for our bacteria. The parts of the plant foods that we can’t digest, our gut microbiome can. People consuming a diet high in plant foods and lower in animal foods seem to have a greater biodiversity of gut bacteria.

- Limit intake of processed foods. Processed foods tend to be void of the polysaccharides and fibers that feed our gut bacteria. Foods high in refined carbohydrates and sugars seem to feed less beneficial species of bacteria as well as encouraging the overgrowth of yeast species. Processed foods can also contain chemical compounds that can inhibit the growth of our gut bacteria and create a less hospitable environment for them to grow in.

- Eat more fermented foods. Naturally fermented foods such as sauerkraut, kim chi, yogurt, kefir, and kombucha contain beneficial bacterial species that can help colonize the intestines and promote the growth of the good bacteria already present.

- Eat foods high in prebiotics that help to feed your gut bacteria including garlic, onions, leeks, Jerusalem artichokes, dandelion greens, asparagus, bananas, legumes, oats, and avocados.

- Don’t eat on the run or when you are under stress. Eating quickly or when you are stressed can decrease your ability to digest your food and can lead to overgrowth of potentially problematic gut bacteria.

- Engage in stress reducing activities such as meditation, yoga, journaling, walking or exercise. High levels of stress hormones can decrease the population of beneficial gut bacteria.

- Consider taking prebiotic and probiotic supplements. Prebiotic supplements can help to feed and diversify your microbiome. Probiotic supplements can help to modify the environment in your gastrointestinal tract to help to encourage the growth of a healthy microbiome. You can find my recommendations for prebiotic and probiotic supplements for general health at Fullscript.

- Go slow when introducing prebiotic foods and supplements. Consuming large amounts of prebiotics can cause an increase in intestinal gas production. To prevent this from happening, it is best to start with a small amount and gradually increase it.

If you would like to know more about the ecology of your gastrointestinal tract, there are stool tests that can identify the bacteria, yeasts, and parasites present. Based on the results of these tests I can make more specific recommendation on how to optimize your “garden within.”

For more information or to schedule an appointment call (207 805-1129) or email my office.